‘He’s a lifer to the game of basketball’: The glory years of Rick Pitino

When Rick Pitino resigned from his position as head coach of the New York Knicks on May 30, 1989, the fabled collegiate program that was about to hire him had slipped and skidded into purgatory. At the University of Kentucky, where the Wildcats captured five national championships in the preceding 40 years, the repercussions from a blockbuster NCAA scandal featuring 18 formal charges — recruiting violations, academic fraud, lack of institutional control, etc. — saddled the team with three years of probation and a two-year postseason ban, the totality of which forced embattled coach Eddie Sutton to resign. Kentucky and its first-year athletic director, C.M. Newton, needed a savior.

Enter Pitino.

Having already taken Boston University to the NCAA Tournament in 1983 and elevated Providence to the Final Four in 1987 — at which point he bolted to the NBA — Pitino had long since established his proof of concept as a high-level program builder with limited resources. The chance to apply his unrelenting work ethic and unbending will at Kentucky, a legitimate college basketball blue blood with arguably the most rabid fan base in the country, was too good for Pitino to pass up, even amid the stench and squalor of NCAA sanctions. He joined the Wildcats ahead of the 1989-90 campaign.

From there, Pitino transformed Kentucky into perhaps the best team of the decade with three Final Four appearances and one national title in six seasons, all while churning out nine first-round picks during that span. He averaged 30.5 wins per year in seasons when the Wildcats were eligible for the NCAA Tournament and delighted fans with a style of play rooted in speed, athleticism, toughness and unmatched physicality.

“I don’t think there could have been another coach in the history of college basketball that could have got Kentucky from where it was when he took it over to where he got it so quickly,” said Travis Ford, a two-year starting guard for Pitino at Kentucky and the eventual head coach of four Division I programs, during an interview with FOX Sports. “And not just talking about X’s and O’s. Yes, X’s and O’s, but also how low Kentucky basketball was at the time. But people still loved it. It was still Kentucky basketball with the fans and everybody. And having to take that over and still live up to expectations, only he could do that.”

The formula for how Pitino did it — with ruthless conditioning workouts, hyper-detailed film sessions, marathon practices and an innovative commitment to personalized player development — tested the upper limits of emotional and physical exertion for everyone on the roster in ways they’ll never forget. That so many of those players respect and revere Pitino to this day, despite the immense challenges he put them through, continues to underscore the power of his coaching elixir.

To better understand that dynamic, FOX Sports spoke with 15 of Pitino’s former players, ranging from his time as an assistant coach under Jim Boeheim at Syracuse (1976-78) through his current role at St. John’s (2023-present), along with the handful of collegiate stops he made in between: at Boston University from 1978-83, at Providence College from 1985-87, at Kentucky from 1989-97, at Louisville from 2001-17 and at Iona from 2020-23.

This is the second in a three-part series titled Postcards of Pitino. We continue with “The Glory Years,” which span Pitino’s stints at Kentucky (national title in 1996) and Louisville (national title in 2013) before his eventual dismissal from the Cardinals in 2017 amid an FBI investigation into fraud and corruption across the college basketball landscape.

[More: Postcards of Pitino: The Early Years]

Editor’s note: The following accounts were edited for length, clarity and flow.

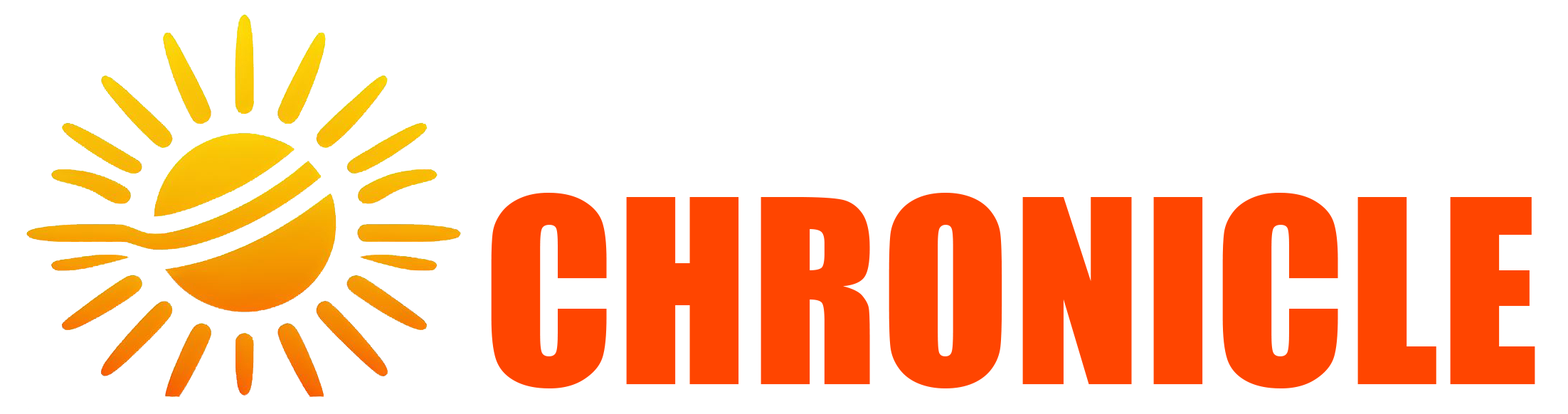

From: Reggie Hanson, F, Kentucky (1987-91)

Career stats: 11.6 points and 5.4 rebounds per game in 101 appearances

Years with Pitino: 2

Kentucky was on probation when Coach Pitino got there, so I was being recruited by other schools to leave. I had my first meeting with Coach Pitino, and my main concern was I’m 6-foot-7 and 180 pounds at that time. I talked to different guys in the pros that played for Coach Pitino, and they were like, ‘Hey, it’s going to be intense, but you’re going to get better.’ And so I told him my main thing was I wanted to get developed into a complete player and not just be a post player. And he said, ‘Oh, you’re not going to worry about that. The main thing you’ve got to worry about is getting in shape.’

The first meeting he had with us as a team, he said, ‘They’re predicting us to not win many games. We’ll win more games than what they’re predicting. I don’t know how many, but we’ll win more than what they’re predicting because of how hard we’re going to work. I appreciate you guys staying, but after preseason conditioning, half of you might be gone because you may not make it.’ And we were all like, ‘Wow.’ But he was brutally honest like that, like you see in the videos with St. John’s. He’s not cutting no corners with you. Either you like it, or you don’t play.

In preseason, we would have 6 a.m. workouts at the track. And if you didn’t make the expected running times, you had to do it again at 3 p.m. If you didn’t make the expected running times at 3 p.m., you had to do it at 6 a.m. the next day. So you had to keep doing it at 6 a.m. and 3 p.m. until everybody had made those times to go onto the next part of conditioning. It was brutal to the point where it gave me anxiety.

Then we started getting to the two-mile runs and things like that. And we had to make the two-mile runs in like 12 minutes. Every day I’d be ready to throw up before we started. And so finally, one day, I got back to where we stayed at Wildcat Lodge, and Coach P. had sent Rock Oliver, the strength coach, over to talk to me. And he came into my room and he said, ‘I need to talk to you, man.’ I said, ‘What’s up, Rock?’ He’s like, ‘Look, man, if you have a problem or there’s something going on, we can get you some help.’ So I’m assuming he thought maybe I was doing drugs or something. And I said, ‘Rock, man, I ain’t never done no drugs, no nothing in my life. I’m just scared as hell before these track runs.’ And he started laughing. He was like, ‘Man, look, I’m going to tell you this: Coach Pitino is going to be on your ass. But just push harder every single day and you will get through it and you will get in shape.’

It’s more mental than physical because the thing about it, once you take yourself to a certain level physically and you want to go beyond that, it’s all about your mind and telling yourself that you can do it. And that’s the whole thing with Coach Pitino is getting you to believe. Getting you to believe that you are so much better than what you were. And so by doing that, he has to push you beyond and make you get beyond the physical part to start thinking like, ‘Damn, I got past that? Yes, I am good. I can do this. I can do that.’ It was hard as hell, but once we got in shape and got to the games, oh man, it was brutal for the other teams.

The yelling and things like that didn’t bother me at all. That motivated me. I liked that energy in a coach. So I came out every day to go as hard as I can. What a lot of players don’t understand is it’s not about how he’s saying it, it’s about what he’s saying. And some players get sensitive to that. And when I was a captain on his first two teams at Kentucky, he used to have me go and talk to players that was real sensitive to that. He is not going to bend. If you ain’t that player, he’s not even going to recruit you because he’s not bending. Either you’re going to be able to take his wrath and get better, or you won’t even be in the program because he’s not bending on his style and how he does it. And he don’t have to.

I was in his office one day and he was showing me, he had this tablet where he made a list of things he wanted to accomplish. He said it could be for the year, for the month or for each day. He said at the end of each day, check off that list and see what you’ve done. And the ones you didn’t accomplish, you’ve got to move it to that next day. And you’ve got to keep on it until you accomplish it.

And then he asked me, he was like, ‘Who was your role model?’ At that time, I said Michael Jordan, Doctor J. and dudes like that. He was like, ‘They can’t be your role models. Can you ever talk to them? No. Can they touch you in any kind of way? No. So they can’t realistically be your role model because you can’t get any information from them to help you get where you need to go.’ At that point, I said, ‘You know what, Coach, after my mother, who is basically my No. 1 role model considering how she raised us, then I would say you, Coach, because you’re teaching me these things that I didn’t know.’ He just smiled.

I’ll tell you one more story about Coach P. that made us really understand how serious he was. We played pickup ball all summer, and we had this guy named Junior Braddy that had played with us. He was going to walk onto the team. And we had our first day, our official first day of practice at 6 a.m., and Junior didn’t show up until practice was over. So Junior walks in the gym and he’s like, ‘Coach, can I talk to you? My alarm didn’t go off.’ So Coach P. looks at him and says, ‘Maybe your alarm will go off next year,’ and walks right off and up to the office. That right there set a tone with everybody.

But we only had seven, eight scholarship players because of the probation, so he came to us and asked the team how we felt about Junior. He asked if we felt like the guy could help us or not. We said, ‘Coach, he’s good enough to help the team, especially in practice and things like that.’ So Coach P. was like, ‘OK, I’ll bring him back to the team. But he has hell to pay for missing the first practice.’

*** *** ***

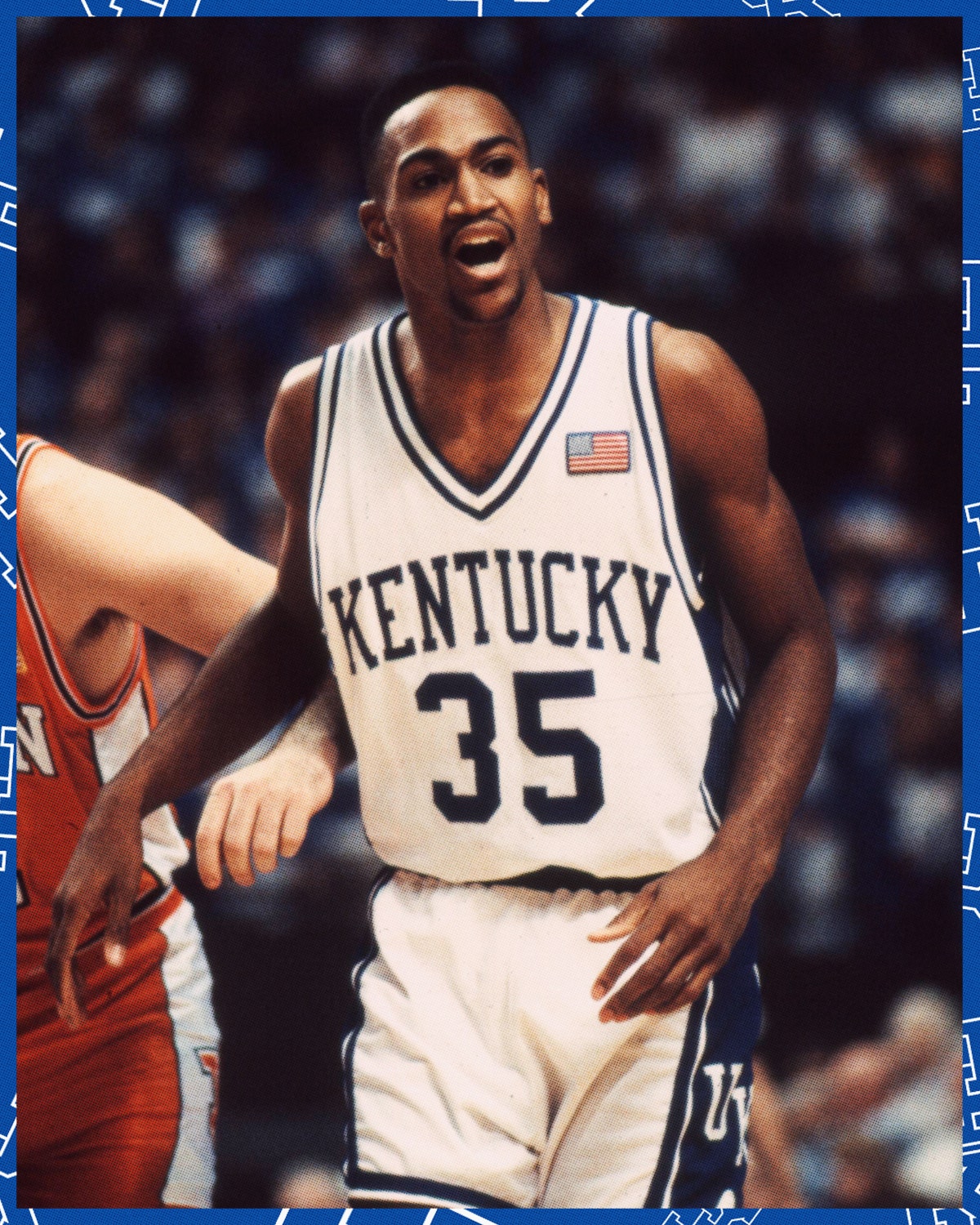

From: Travis Ford, G, Kentucky (1991-94)

Career stats: 8.1 points and 4.1 assists per game in 130 appearances

Years with Pitino: 3

I was a college head coach for 27 years, and man, how times change. I couldn’t even begin to imagine putting one of my teams through what we did back then. I mean, it would be unheard of. We conditioned six days a week. And as you probably heard, we jogged over a mile to the track, just to get to the track. You had to jog there at 5 [o’clock] in the morning, and then once you got there, we never knew what we were going to do, but we knew it wasn’t going to be any fun. And then when it was over, you had to jog back. Those are not fond memories whatsoever.

What I learned more and more when I became a coach was that Coach Pitino’s workouts were more about the mental than it even was the physical. I learned so many things when I became a coach that showed me why we did certain things. Yes, it got us in elite shape, the best shape of any team in the country, without question. I think we knew at the time that nobody else was doing this. But what we probably didn’t know as a player is that Coach Pitino was making you do something that you never thought you could do and developing a mentality to fight through pain, to fight through a moment where you’re like, ‘I can’t do another sprint, I can’t go around this track one more time. But you don’t have a choice. You were scared of the consequences. You didn’t want to let your teammates down. And you figured out, hey, I didn’t think I could do one more — but I ended up doing maybe five more, 10 more. So, no question, it was as important to build mental toughness as it was just to become in great physical shape.

My relationship with him today is as close as ever. I love him to death. If he said right now, ‘Hey, I need you to come help me do this,’ I would be there. I couldn’t tell the guy, ‘No,’ for anything. I attribute so many things to him that I’ve been able to accomplish. But if you told me when I was playing for him that I would have that bond eventually — because there’s many days when you’re just like, ‘This guy…’ Playing was the most fun I’ve ever had, was the most enjoyable time of my life, the experience was great. But it was also the hardest thing I’ve ever done, playing for him. It’s not easy. It’s not for everybody.

I don’t think he’s as hard today as he was then, that’s for sure, but when you’re sitting in a room with him and he’s talking to you in the locker room, or he’s talking to you on the court, you know he’s right. You know, ‘I better listen to him because if I do, our team has a chance to have great success, and it may help me as an individual player.’ You just believed in him. And for somebody like me who was obsessed with basketball and obsessed with trying to be the best I could be and I loved winning, I’m just like, ‘I may not like it, I may not particularly be enjoying it at that particular moment, but if he says do it, it must be the right thing to do.’

He invented the individual instruction. I don’t know if “invented” is the right word, but he was the first one to ever do it. He was the first to ever bring guys in between classes and do it. No one was doing that, not on a structured basis. We knew Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday when our individual time was from the get-go. It’s 45 minutes non-stop. It’s not just shooting. This was one-on-one. This was game-type shots. This was timed shots where you’ve got to make so many shots in a given amount of time. Again, very similar to the conditioning in that it was testing you mentally as much as it was physically. I loved it. I absolutely loved it. Whatever player I became, I think it was a big part of spending that time with him and assistant coach Billy Donovan in practice.

Today, everybody kind of does individual instruction in the preseason. But most coaches don’t do it once the season starts. Oh, no. Even today, Coach Pitino’s guys are still coming in daily to do individual instruction. It never changes. That’s the difference. The commitment to it and the level of intensity of every single one is what’s different.

*** *** ***

From: Tony Delk, G, Kentucky (1992-96)

Career stats: 14.2 points and 3.5 rebounds per game in 133 appearances

Years with Pitino: 4

He came to speak at a banquet my senior year of high school, so that was really my first time meeting him. Afterward, we were walking back to my house and he was just telling my parents he would take care of me. I think what really sold my brothers was when he spoke about the NBA. They were like, ‘Oh, NBA?’ So that got them excited about the potential and possibility of making it to the next level.

I really didn’t know how tough it was going to be until I went through my first individual instruction. My teammate Rodrick Rhodes and I were like 15 minutes in, and we were both exhausted. There was nothing left in the tank. I can remember Pitino just calling us both ‘pampered freshmen’ and I think he said, ‘Hey, you guys are done. You can’t give me anything else.’ That first individual instruction was tough, and then the two- or three-hour practice later that day was even harder.

In individual instruction, you’re really working on your ball handling, your shooting, some conditioning. That was your time to work on your craft so that our games never fell off, you know? Because I think once kids start playing, they forget, ‘OK, I’ve still got to work on my ball handling, I’ve still got to work on my shooting,’ so he made sure that was incorporated in all of our practices.

He gave us so many drills and he taught us so much about the game — and it wasn’t just as collegiate players. Even when I became a pro and did some coaching, started my own training program, there’s still a lot of drills and things that he taught me that are still favorable to this day. The guys you talk to usually always mention we had to make 170 layups in four minutes. Left hand, right hand, running full speed — that was a conditioning drill. It was hard, but like I said, it really built mental toughness when you didn’t know you could put your body through what he put on the table, you know? So you really believed in everything that he was saying because by the time we finished playing in ’96, we won a championship. So the work we put in definitely paid off. The reward was there.

For me, the X’s and O’s stuff was brand new. Just the whole scouting report, breaking down film and understanding team tendencies, taking player tendencies away, understanding our plays, how to set a guy up, how to get open, how to set a good screen. He taught us so much about just the game itself, and then the key to the X’s and O’s execution part was, you know, being in the right place and being there at the right time. And then the individual instruction really helped me make shots because what we’d do in individual instruction was part of our game plan on offense. So he knew how to transition certain things into the actual game. He knew how to simulate the game in certain practices and drills so then it made the game that much easier. And then the practices were 10 times harder than games. We couldn’t wait for an actual game because it was like, ‘Finally, we don’t have to practice!’

Probably the most pressure he had was our senior year, the ’95-’96 season. We started out the season ranked No. 1 in the country. Before that, you know, he came and basically kind of like rebuilt the whole program. But the more you start getting talent, and once you go to a Final Four, I think the expectation changes. How do you sustain that? You’ve got to start getting guys that are going to be next-level players. And when you bring all those guys in, now you have a lot of different personalities. And he knew how to mesh the chemistry. He knew how to play certain guys. But when you play up-tempo and you play that hard, he knew you were going to come out of the game at some point in time. You were going to be exhausted. So it was smart on his part to play up-tempo to get everybody playing time, enough playing time where they can get numbers.

He made us work extremely hard on defense and we had to sacrifice a lot. But he gave us freedom on offense, and I think that’s what guys really enjoyed about his style. We played fast and we had guys that could execute, that could make that decision under duress, and that was the key to us practicing the way we did. More NBA scouts probably wanted to see us practice than wanted to see us play in the game, because that’s when we really, really got after it.

The game is his baby. There’s nothing that comes before basketball other than his family. All the time he spent with all of us, you know, it speaks about who he is as an individual because he sacrificed so much of his time for myself and hundreds of other players that have come through the program. It’s his love for the game. He’s one of those guys when I think about coaching lifers, that’s what he is. He’s a lifer to the game of basketball.

*** *** ***

From: Larry O’Bannon, G, Louisville (2001-05)

Career stats: 8.8 points and 2.4 rebounds per game in 130 appearances

Years with Pitino: 4

It was tough, man. Just the commitment that he expected was something that I had never really known. You read about it and you hear about it, but until you’re in it, you never really know. He was intense when it came to everything, man. I think you just saw the competitive nature grow over time within the program. You could see the work ethic, the level of expectation from guys, it just trickled on in and became a culture of guys getting in the gym in the summertime. We had competitions every week in the weight room. We had these charts that kept track of who was the leader for holding the weight the longest, who bench pressed the most, who squatted the most. It just became a culture of competitiveness and just wanting to get better.

The individual instructions that we did every day was his teaching. That was the difference. You show up and you go through a bunch of rigorous shooting drills, a bunch of ball handling, full-court one-on-one. Footwork was a big emphasis. He was a big pet peeve guy on traveling. He hated if you traveled given the amount of footwork drills and shooting and preparation that we did. He was really intense about reading the ball. That was a big thing for him, reading the eyes of the passer. He would always say, ‘Read the eyes of the passer. There’s not many great passers in college basketball. They tell with their eyes where the ball is going.’

A lot of his teachings with the press and how to read and knowing what position to be in, the individual instruction was a lot of times where he taught us a lot of things. You break it all the way down to one-on-one. Then you build it up two-on-two. Then you build it up three-on-three. Then you build it up four-on-four. Then you build it up five-on-five. So when you’re building it from the very bottom, you know every facet of the press: where you’re supposed to be, where everybody else is supposed to be, where you’re supposed to be reading. Sometimes you’d be pressing and we’d have more than five people, you’d have seven people out there sometimes. He just knew his systems and how it was supposed to work, and he broke it down for us to where we could really understand it.

The film breakdown was phenomenal. They made the game easier and the scouting report easier and you understood it. But then when you leave and go play someplace else, and they don’t take it as serious, or it’s not as detailed, you’re like, ‘Man, I kind of wish I had these same scouts.’ Because it didn’t matter how long until our next game, we had film every single day. After four years of watching film and learning how they do it, you almost become kinda automatic with knowing how to break teams down and the guy you’re guarding:

Can he shoot? Can he play the pick and roll? How does he defend the pick and roll? How does he defend one-on-one? How does he defend when someone is cutting? Is he able to get cut back-door? Does he guard well coming off of stagger screens? What’s his weakness?

But the basis of it all was conditioning. You had to be conditioned to be able to play that way. It’s funny because once you understand that and reach the conditioning levels that he wants, it’s almost kind of like you get tired and it becomes like an autopilot because you’re so used to fatigue that you learn how to function in it. And so when you’re fresh, it almost makes you question yourself like, ‘Damn, am I playing hard enough?’ And so then it’s like once you kind of get tired, your body just goes into a trance.

It took some time to adjust to his style. But you learn that outside those lines, he’d do anything in the world for you. Once you step outside the lines and you call Coach Pitino, he’s right there. Probably the best advice he gave me was not even related to basketball. Once I finished playing at Louisville and I was going to play professionally, he told me to invest 75% to 80% of my contract — the first two years of my contract — into the stock market. Best thing he ever told me to do.

But in between those lines, it’s a different animal. And he turns you into a different animal. His personality rubs off on his players. Cutthroat, win by any means necessary, do whatever it takes to win — that rubs off, man. And yes, he can be really tough and really rough verbally. At times, he made it a point to try to get under your skin to motivate you or piss you off because sometimes it might make you play better. But that’s why he had great assistant coaches. The assistant coaches love on you, build you up, and tell you, ‘Hey, just listen to the message,’ because it’s tough sometimes for 17-, 18-, 19-year-old kids. But like I said, once you kinda get a year or two up under it, you kind of understand, ‘All right, Coach,’ and you learn to listen to the message and not how the message was sent to you.

We went to a St. John’s game when they played Xavier. He still had the same lines, the same curse words, the same curse phrases, the same exchanges. He’s got a few new ones in there, but he’s still fiery and getting up in guys and still competitive, wanting to win. So it’s a pleasure to see him still at it and still have that fire lit in there to win. I think he’s really in a great place.

*** *** ***

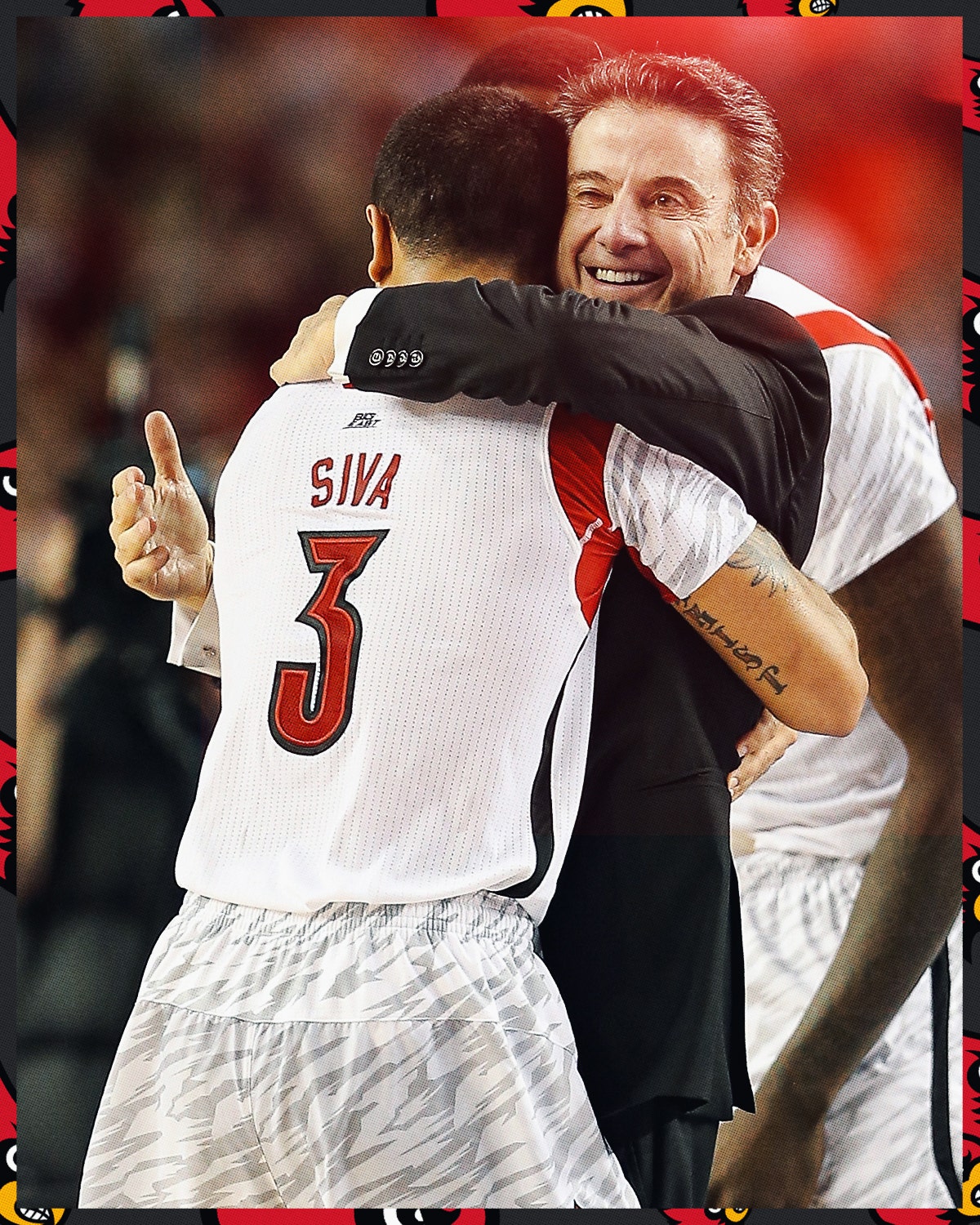

From: Peyton Siva, G, Louisville (2009-13)

Career stats: 8.4 points and 4.7 assists in 144 appearances

Years with Pitino: 4

Coach P. has just always had a presence about him. He’s an amazing speaker. He does a great job motivating his guys. When I was being recruited by him and going into the locker room, listening to postgame speeches and things of that nature, I just remember he sounded electric and I remember how engaged the guys were. It was next-level.

When I first started watching Louisville play, especially in high school, I remember thinking, ‘Oh, man, they play so fast. They get up and down, they run. It looks like a fun system to play in.’ And I didn’t choose other schools because I was like, ‘Aww, man, I don’t want to play any defense. I just want to get out there and play and run.’ And then, lo and behold, once I get there, it’s all about defense, defense, defense.

A couple of freshmen — me, Mike Marra, Rakeem Buckles — we did our first individual instruction and, you know, the older guys were fine. Me and Mike? We needed oxygen tanks. We were laying on the floor in our locker room. We didn’t know what to expect, you know? We didn’t really have trainers around then, and so that was kind of like our first real individual workout. I thought we were just getting some shots up. No, it’s one-on-one full court, it’s sprint-away 3-pointers, it was different. But after the first couple months, first couple weeks of doing it, you get the hang of it and you know how to condition yourself. You know that you’re in for a hell of a ride.

My junior year, making it to the Final Four, it was a magical run. We thought we were good and we believed we were good, but there wasn’t really no high expectations of us making it that year. But we had a really good run through the Big East, won the Big East Tournament, and just continued to use that momentum. Coming back my senior year, we just felt like we could win it all. Getting a taste of that Final Four, knowing what it felt like to get there, we knew what we could do to get there again and win. Coach P. just kind of continued to hold us to that standard, wouldn’t let us take our foot off the gas.

That season, we lost three games in a row to Syracuse, Villanova and Georgetown when we were ranked No. 1. And it kind of put a bad taste in our mouth. But we had some self-reflecting going on and Coach P., he probably wanted to jump off a bridge at that point in time. We felt like we had a good team. We felt like we had great leadership on our team. And there was just sacrifices we needed to make. And Coach P. really just continued to put trust in us, push us. I can’t emphasize enough just how he was holding us to the highest standard, you know?

I hated all the hours of film study that we did. ‘We went over these guys a million times. We watched this clip a million times.’ As a player, you don’t realize what he’s kind of teaching you and ingraining in you so that when the game comes, there were points in time on the court when I knew the other team’s plays better than they did. And I was like, ‘Hey, you’re not supposed to be here right now.’ It just goes back to the film study that we did, the attention to detail that we did, and all the times that he would get on us and just talk about the little things that we would just find annoying. As a coach, I really respect that now because it’s those little details that matter at the end. And if you let your guys slip up in those little details, and if you don’t have that foundation and that base, everything is going to come unraveled.

From a player’s perspective, you kind of look at Coach Pitino as this almighty character and you don’t really want to say anything to him. He’s like this great father figure to a lot of the players. As a coach now, I feel more comfortable asking questions. You still have that respect factor for him, but you can kind of just speak a little bit more freely. I mean, he still might yell at you. But you kind of know that I’m an adult now, I can go home to my family and don’t have to worry about him trying to make me run on the treadmill anymore.

Coming Thursday on FOX Sports: Part 3 in our “Postcards of Pitino” series exploring Pitino’s return to college basketball at Iona (2020-23) and St. John’s (2023-present). Here is a link to our first story that looked at Pitino’s early years in coaching: Part 1: The Early Years

Michael Cohen covers college football and college basketball for FOX Sports. Follow him on Twitter @Michael_Cohen13.

Want great stories delivered right to your inbox? Create or log in to your FOX Sports account, and follow leagues, teams and players to receive a personalized newsletter daily!

Get more from College Basketball Follow your favorites to get information about games, news and more

editor's pick

latest video

Sports News To You

Subscribe to receive daily sports scores, hot takes, and breaking news!